It might surprise you to hear that the way I first learned about Vampire Weekend (from an iTunes Free Single of the Week) was somehow less uncool than the way I first started liking Vampire Weekend (because I felt like I had to in order to be cool).

It’s no coincidence that this was the mid-2010s, around when I started working at Urban Outfitters on college breaks—ostensibly to “understand hipsters from the inside out,” but obviously because I wanted to be a hipster. What that actually meant to me was a bit nebulous, but I knew that I (a clean-shaven, boat-shoe-wearing boy from suburban Texas) was not it (a mustachioed, flannel-wearing Brooklynite, maybe). My co-workers at Urban were a lot closer to my idea of hipsters, and so I treated those summer and winter breaks like studies abroad, trying to learn the subtleties of wearing beanies in 100-degree weather and listening to bands that sounded like industrial machinery from the locals, all while trying to disguise my non-hipsterdom in the clothes I bought with my employee discount (too late, I learned that my Sperry Top-Siders gave me away).

In retrospect, it was a funny case of privilege envying privilege. I feared that my sheltered, buttoned-up upbringing had insulated me from the kinds of lived cultural experiences that might indie-fy someone, when in reality, many of my coworkers were from near-identical backgrounds as me but simply had better style and more interesting taste. No matter—I felt like I was getting cooler through osmosis, and our store’s well-stocked vinyl section gave me an idea of what artsy young people were listening to (or at least what a corporation aimed at artsy young people thought they were).

Chief among our record stock was Vampire Weekend, whose bright guitars and literary pretensions had mostly sailed over my head up to that point. But something about the acclaim for their third album (even then, I was no stranger to piggybacking my taste off of Pitchfork’s “Best New Music”) and their affirming collision of styles (you can wear boat shoes AND be cool?) eventually made me want to like them, and so I gave it another, more successful effort.

The funny thing about my transparent hipster posturing is that, to some degree, it worked. At least at Texas A&M University in 2015, it didn’t take much more than a denim shirt layered over a graphic tee to get deemed comparatively “alternative” in a sea of Comfort Colors sorority shirts. And in some ways, my conscious curation of a musical taste that extended beyond Ben Rector and Judah and the Lion was just an auditory denim shirt, a facade of coolness that might get me credit for being “hipster at A&M” but would still make me the most boring normie in Williamsburg.

There’s a reason I’m even bringing my school into this, because I’d be lying if I said that Vampire Weekend’s Ivy League bona fides weren’t part of their appeal. Texas A&M is a massive, publicly funded “state school,” an objective classifier that I’ve learned since living in New York can have a strongly pejorative connotation. I resent that—not because I’m ashamed of getting a public education (I’m very proud of my alma mater for both its academic caliber and its accessibility), but because of the implication that I should be.

And yet, for all my school pride, I’ve retained my fascination with Vampire Weekend’s Columbia and the Ivy League in general. Maybe it’s curiosity about a road not taken (could I have gotten into an Ivy if I’d applied myself better in high school? Nope, but it’s fun to pretend), or perhaps it’s the general mystique around liberal arts colleges that allows me to imagine idyllic lawns full of readers and classrooms full of Socratic seminars. Either way, I’ve always had a split mind on the topic, somehow feeling both inferior (I’m no upper-class whiz kid) and superior (I’m no entitled, New England prep prince) to my Ivy peers.

In that way, Vampire Weekend was a hack for me to have it both ways. Who needs to pay for a pompous, blue-chip education? We’ve got everything we need over here in true grit, country-strong, proletariat America (this gets funnier the more you know about Plano, TX—but it’s how I felt). But yes, now that you mention it, I am a little bit more cultured than your average Aggie bumpkin, on account of my cuffed jeans, and my having read Infinite Jest, and my enlightened love for Vampire Weekend. Note my knowing smile when the boys sing about Oxford commas; see how natural a fit they are for a guy like me—a guy who worked at Urban Outfitters, mind you.

And here’s where I admit that I love having cake, and I really love eating it too. Vampire Weekend might be the clearest example of the kind of “cool” I simultaneously chase and disown, but it’s far from the only case. There’s a reason I cling to my coastal elitism when in Texas and to my unassuming southern outsider status when in New York; I’m nothing if not interesting, by which I mean if I’m not interesting, I’m nothing. It’s no mystery why I’ve always identified with the scene in Juno when Juno tells Paulie, “You’re, like, the coolest person I’ve ever met, and you don’t even have to try.” “I try really hard, actually,” Paulie replies. I want to be cool without having to try—but if I have to try, I will.

Without knowing it, I chose the perfect avatar for my trying/not-trying paradox in Vampire Weekend, whose prestigious degrees and clear intelligence have always been undercut by a wry self-awareness. Don’t forget that when they sing about Oxford commas, they sing about not worrying about them so much. And though the boat shoes and polos they used to don superficially matched their background, they always seemed to be wearing them with a half-wink. In simultaneously showing off and sending up their pedigree, they get to have their privilege and cheat it too, highbrow and lowbrow living on the same smirking face.

Of course, unlike me, their self-contradictions are actually generative, producing complex, interesting art. Their first two albums, Vampire Weekend and Contra, share a similarly bouncy pop-rock sound that both typifies and improves upon the late-aughts indie style. Besides the fact that their tunes are catchy and their rhymes fun, VW’s self-constructed role as learned cultural pundits also allows them a built-in defense for any criticisms. Their Paul Simon-esque Afropop guitars aren’t appropriation, they’re homage. Their lyrics aren’t pretentiously verbose, they’re satirically verbose—unless you’re impressed or moved by them, in which case they’re sincerely verbose.

Some of this is certainly projection, as it’s more palatable to think that a band that offers me the ability to claim as much or as little of their coolness as is convenient is playing some of the same evasive self-image games as I am. And those criticisms of calculated self-consciousness ultimately break down as you get deeper into their discography, which leaves much of the campus-friendly wit behind in favor of a more expansive sound and a more searching gaze. Modern Vampires of the City does away almost entirely with the boppy guitars, trading them in for golden pianos and orchestral swells to score an honest wrestling match with faith itself. Father of the Bride is something else entirely, mixing Phish-inspired jams and sunny Van Morrison riffs with dabbles into electronic, psychedelic, and country (?) music. By this point, if you were to accuse them of trying too hard to be something, you’d first have to define what that thing was.

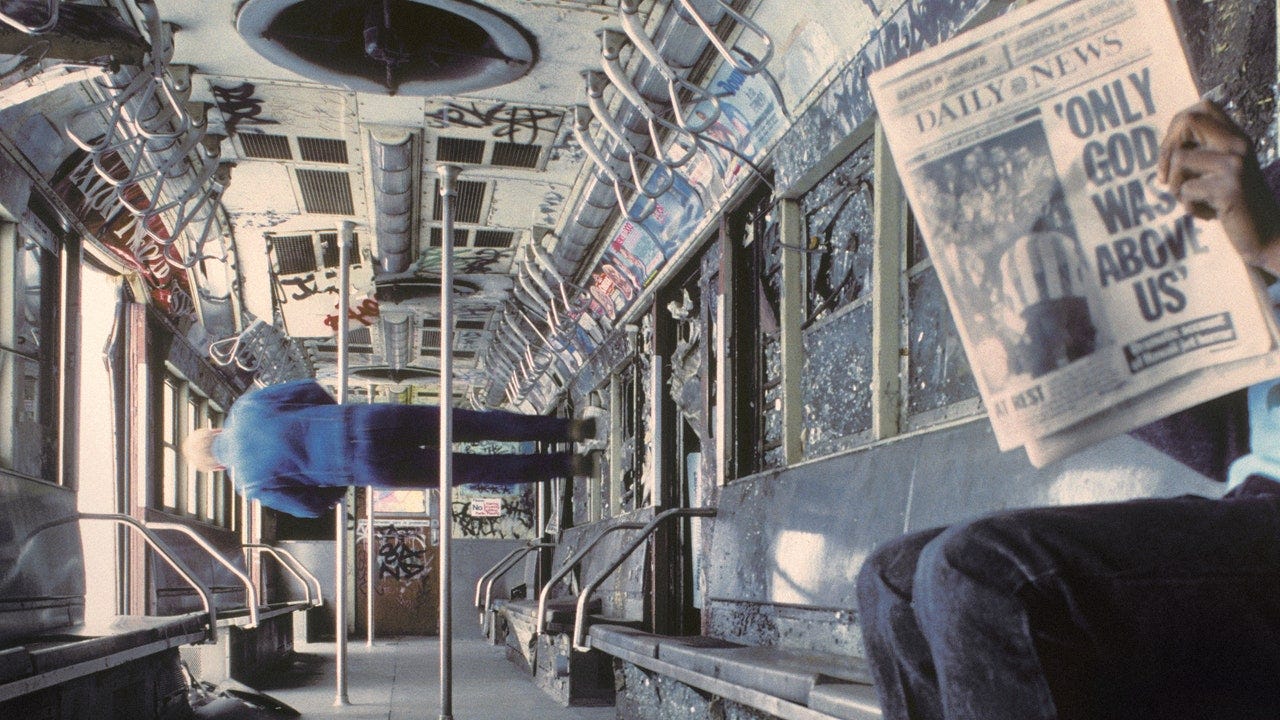

All that polymathic exploration brings us to their new album, Only God Was Above Us—which, quite frankly, rocks. Whereas MVOTC and FOTB felt like distinct departures from the core VW sound, OGWAU feels like a collage of everything they’ve ever done while managing to push their holistic project forward. Its compact tracklist has songs that would sound at home on each of their past works—“Prep-School Gangsters” could fit on either of the first two albums, and “Classical” has a riff that could slide right alongside “Sunflower” on FOTB—and I’m especially excited about the return of baroque piano and string lines a la “M79” or “Step.” This was always the most idiosyncratic ingredient in their musical stew, and hearing it pop up again on “Ice Cream Piano” or “Capricorn” is a reminder of just how creative the band can be while remaining under the banner of “indie rock;” suffice to say, you couldn’t trace many of their contemporaries’ influences back to Handel and Bach.

But even the tracks that stick closest to VW’s established sound have interesting new textures. Take “Capricorn,” whose basic structure and lyrical cadence echo songs from MVOTC, at least until the song is trampolined into fascinating new territory by loud, cacophonous horns (or slide guitars? Something’s screaming, that’s for sure). Or there’s “Mary Boone,” whose background choirs recall “Hold Me Now” or “Big Blue” from FOTB, but whose unexpected drum-and-piano-break catapults it into musical no man’s land. (And possibly, into the echelon of the greatest songs ever written? But I’m being hasty.) There are also plenty of songs on OGWAU that have no clear precedent, like the erratic, skittering “Connect,” or “The Surfer,” which could be the theme song to the strangest Bond film never made.

Despite the diverse array of sounds, the album is bound together by a cohesive lyrical theme: empires rise and fall, “the cruel, with time, becomes classical,” and civilization marches on through all the absurdity. While that kind of big-picture contemplation could easily slip into cynicism or even nihilism, there’s a zen-like optimism to VW’s outlook. If you can’t override all the chaos of modern (and historical) life, maybe you can make a fragile peace with it, surfing the cacophony and enjoying the ride. That seems to be the lesson implied by ending the album with a buoyant song called “Hope,” in which the boys follow a list of grievances both trivial and eternal with the same liberating advice: “I hope you let it go.”

Perhaps there’s something for me in that advice, too. As with many things in my life, I pursued a fandom of Vampire Weekend with ulterior motives but ultimately learned to love them on their own merits, their quality transcending my shallow aspirations. For as much as I hypocritically encourage friends to “like what they like,” I could probably take some of my own (and VW’s) advice and just let the pretensions go.

They’re right, after all; time has passed. I’ve ditched the Sperrys, I have the mustache, I live in the city. I’m no hipster, nor do I try to be (maybe the writing was on the wall for That Whole Thing when a corporation like Urban was selling us pre-packaged counterculture), but I’m also something in between who I was in college and who I figure I’ll be in another decade. To the extent that I still aspire to an elusive coolness, at least I’m trying to sabotage those efforts by writing about them here.

Only God Was Above Us is a great enough album that I don’t need the added thrill of its cultural cachet to enjoy it, and at least now I can admit how dorky it is to feel a little cool and a little smart just for liking a particular band. Of course, I can also admit that I do still feel a little cool and a little smart for liking this particular band. But hey—they keep giving me cake to eat! What am I gonna do… not try to have it, too?