It’s Sunday night, 9 PM, and I’m doing what every other person (A25-49) is doing: firing up Max, née HBO, for their latest water-coolery offering. This seasonally affected time of year, that means Issa López’s True Detective: Night Country, a sort of spiritual sequel to Nic Pizzolatto’s much-memed (and very good) first season that subs Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson for Jodie Foster and Kali Reis.

Like most people (A25-49), I’m enjoying this shortened season. Foster is Trying and it shows, and her bristly dynamic with Reis is as interesting as her bristly dynamic with half a dozen other characters (she’s got a way with words). Better still, the perpetually crepuscular setting of Ennis, Alaska is spooky and singular even before it’s revealed to be a sort of permeable borderland between the living and the dead. Or maybe people are just tripping off the poisoned mine water? We’ll have to see.

If I have a main criticism, it’s that some of the mystical, what-if-the-evil-we’re-facing-is-bigger-than-we-realized of it all feels a little more put-on than in Pizzolatto’s take. Some of the scares are cool and fresh; others feel like obligatory stabs at supernatural suggestion rather than organic developments of the story.

The writing can also be a little touch and go. There are bits of subtle characterization (one character asking another if she still keeps her groceries in the same cupboard), and then there are exposition dumps hardly more elegant than “He was in the Amazon with my mom when she was researching spiders right before she died.”

Still, if López is working with somewhat of a blunt instrument at times, at least she’s using it to carve interesting shapes out of the ice. The show has enough going for it (Corpsicle! at the Ice Rink) to more than hold my attention, and I’m enjoying having something worthy of the water cooler after a long drought. And really, even my light criticisms would probably hold less weight if they didn’t have the inconvenience of being held in direct Sunday night comparison to another 6-episode detective show that’s just as chilled, but in a completely different sense.

As soon as I finish the latest Night Country ep each Sunday, I drop my latitude along with everyone else (A55-69) to AMC+, where I thaw out with the warm, South-of-France pleasures of Monsieur Spade. If there ever existed an anti-water-cooler show, it’s this one; despite being written and directed by Queen’s Gambit auteur Scott Frank, nearly every conversation I’ve had about the show has begun with the threeish minutes it takes me to explain its concept and ended with the threeish seconds it takes them to politely go “ohhh.”

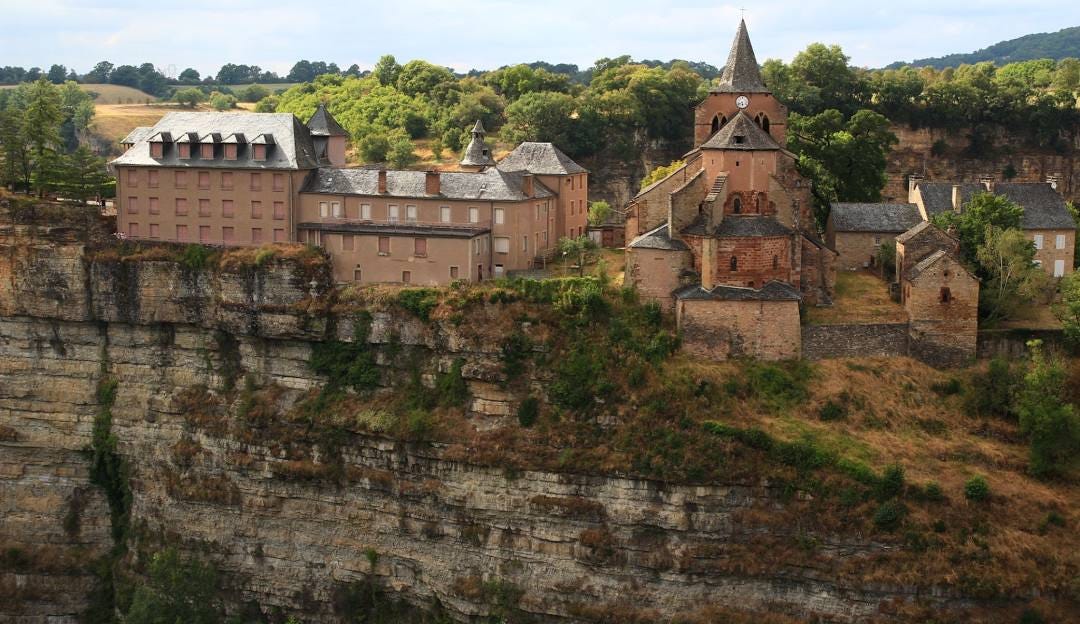

And I’ll admit, it’s not exactly the Tower of Terror of elevator pitches. Set in the 60s in Bozouls (a beautiful French commune built on the edge of a gorge), the show picks up years after the 1930 novel (or the 1941 film) The Maltese Falcon, with iconic detective Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart then, Clive Owen now) delivering the progeny of his late femme fatale to the girl’s estranged father. Expecting an in-and-out job, Spade instead winds up kicking the bad dad out of town, marrying a local widow, and becoming embroiled in the murder of six nuns.

That sextuple-murder would seem to set up a webbed mystery similar to that of Night Country’s sextuple-murder, and it does launch Monsieur Spade into a somewhat labyrinthine plot involving jazz clubs, the Algerian War, landscape painters, and the Vatican. But what distinguishes Spade both from this iteration of True Detective and from most of the mystery fiction I love is that its primary thrills have almost nothing to do with who- (or even really how- or why-) dunnit. Instead, they have almost everything to do with Clive Owen.

Or at least, with his entire… je ne sais quoi. It’s almost hard to put in words, but the way Owen puts his words—a wisened Brit playing a wisened San Franciscan speaking broken French—is so rich, so weathered, so soothing. He’s doing Bogart, sort of, but he’s also doing his own kind of ASMR detecting, chasing down leads with a quiet, exasperated determination that makes you just as sure that he’ll solve it as that he couldn’t do so if he were moving a millisecond faster or slower than he is.

Just as the cinematography paints The Maltese Falcon’s black-and-white noir in a fresh coat of warm, golden-green hues, so the writing brings its quippy dialogue into (relative) modernity. Characters still talk like they’re playing pinball, but there’s a bit more world-weariness in the old private eye’s tone. If he was already skeptical of his world of liars and thieves back in the 30s, then a couple of decades in the sun and some personal tragedies have convinced him the whole world’s just as crooked, even if they’ve also shaken him open to at least the possibility of love. Not—as his constant wit makes abundantly clear—that that’s any excuse to stop letting the zingers fly.

The show at large mirrors the calm, complex pleasures of Owen’s performance. Most of the other characters are French, and forget speaking—their entire manner of being feels molded to a south-of-Paris tempo that isn’t slow or unserious but simply unhurried. When confrontations happen, they’re usually over cigarettes or omelets. Shootouts and car chases sometimes erupt, but normally with enough of a breather for us to always maintain our bearings. And if that’s how the show plays the moments of “tension,” imagine how lush and relaxed its flirtations are: between men and women, or girls and clothes, or Spade and death (he’s diagnosed early on with emphysema, a message his doctor delivers over a cigarette). Everyone is fun, or funny, or beautiful, or fascinating, and despite being leisurely at times, the show is never, ever boring.

The sensorial joys extend to (emanate from?) even the sound design, which is the crispest I’ve heard this side of Better Call Saul. Shoes crunch gravel, suits crinkle and stretch, cigarettes softly burn (come to think of it, the emphysema’s not really a surprise). Then there’s the score by Carlos Rafael Riviera, which wraps the whole thing in velvety trumpets and twangy guitars. Even the smallest stone feels considered, and together, it all achieves a kind of three-dimensionality that makes Spade a pleasure to watch, or listen to, or feel, even when you completely lose the plot.

(If you listen to this and think, “that’s sick,” then you’d probably watch the show and think, “that’s sick,” too)

That’s where I come back to True Detective, exactly halfway through both shows’ runs. And true, I’m writing about two mystery shows at the worst possible time, before they’ve had a chance to roll up their sleeves. But that gets at what I’m getting at; while I’m enjoying both shows greatly and am arguably even more interested in Night Country’s “solution,” I’m more confident in Spade to stick the landing it doesn’t even seem primarily interested in.

Maybe that’s because it’s just as intelligent in the subtle ways it has characters greet each other as in the ways it has them kill each other, or perhaps it’s because easygoing confidence inspires so much more of the same than Night Country’s harder-efforted achievement does. And despite the faith I have that Frank and Owen will pull it all together in a satisfying finale, the fact that each moment-to-moment scene is such a pleasure (count how many times I used that word while talking about the show) means there’s less at stake if they don’t.

For an Agatha Christie-head like me, even pitting these two shows against each other is a position at odds with itself; the more mysteries the better, and these two are both good in unique ways. It’s just—as someone usually obsessed with plot—my surprisingly clear preference for Spade suggests that, at least to moi, one of them might be great.